Thursday, November 23, 2006

It's interesting that the readings from this week talk about biopolitics & control, because we also talked about ideas of control (albeit in a different way) in my Nutritional Anthropology class on Tuesday. But I will get into this later.

Lazzarato cites Foucault as saying that we should "speak of power relations rather than power alone, because the emphasis should fall upon the relation itself rather than on its terms". I agree with this statement because although it does seem as if the dominant is overpowering the submissive in general ideas of power, this is not the case. There is somewhat of a dynamic that exists between the 2 parties. The dominant is controlling the submissive, but it must beware of possibilities that the submissive may resist. The dominant must also have certain qualities to be able to assert whatever power that they have. I guess these could include a legitimate threat, informational power, or superficial qualities such as appearance. In my Applied Social Psychology class, we talked about such characteristics as being determinants of whether people will conform to norms, or be persuaded by various advertisements. One could say that advertisements are a way for the government to covertly "control" us, because advertisements always contain subliminal messages.

This concept of institutions inadvertently controlling us is what we talked about in Nutritional Anthropology. One of the readings written by Marjorie DeVault, talked about Japanese obentos (intricately designed lunchboxes) and how their preparation situates the obento producer as a woman and a mother, and the consumer as the child. The Japanese nursery school is seen as a primary "ideological state apparatus" (an institution whose role is not political or administrative, but that still manages to influence us). It makes people see the world a certain way, and to accept certain identities. In this case, although it has less to do with technology, the mother and child are put into their respective positions due to the covert influence of the education system. The idea of power relations can be discussed here too, because what's interesting about this dynamic is that although the mother is placed into this position, it is not an unenjoyable one. She takes pleasure from preparing these lunchboxes for the child, as they are the way for the Japanese mother to express her identity and commitment through her food. So, a person's autonomy is not completely lost through this wielding of power, although they are ultimately still restricted by these rules.

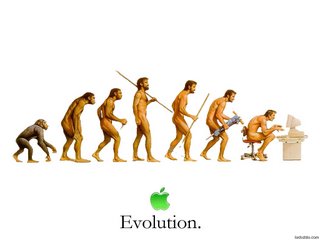

The other reading we focused on this week was Sloterdijk's chapters from "Critique of Cynical Reason". What I found interesting was a reference that he makes in the chapter on artificial limbs. He mentions that in some textbooks, "a highly apposite image of the human being emerges: Homo prostheticus". Is this idea of a new species of human being a relative of the cyborg? Perhaps, since he is part machine and part organism. I actually plan to talk about transhumanism in my research paper, and this passage sort of touches on this matter. The fact that some textbooks and writings give humans with prosthetic limbs a whole new name implies that they are post-human beings.

On the topic of biopower & biopolitics, it might be interesting to bring up the issue of cancer drugs not being available to everyone in Canada. "Government red tape" apparently has strict rules about who gets the drugs and who doesn't, which is incredibly unfair in a situation that may be a matter of life and death for the cancer patient. An article about this issue can be read here. Another example of power over drugs is the Ontario Drug Benefit Formulary, which can be read about here.

Lazzarato cites Foucault as saying that we should "speak of power relations rather than power alone, because the emphasis should fall upon the relation itself rather than on its terms". I agree with this statement because although it does seem as if the dominant is overpowering the submissive in general ideas of power, this is not the case. There is somewhat of a dynamic that exists between the 2 parties. The dominant is controlling the submissive, but it must beware of possibilities that the submissive may resist. The dominant must also have certain qualities to be able to assert whatever power that they have. I guess these could include a legitimate threat, informational power, or superficial qualities such as appearance. In my Applied Social Psychology class, we talked about such characteristics as being determinants of whether people will conform to norms, or be persuaded by various advertisements. One could say that advertisements are a way for the government to covertly "control" us, because advertisements always contain subliminal messages.

This concept of institutions inadvertently controlling us is what we talked about in Nutritional Anthropology. One of the readings written by Marjorie DeVault, talked about Japanese obentos (intricately designed lunchboxes) and how their preparation situates the obento producer as a woman and a mother, and the consumer as the child. The Japanese nursery school is seen as a primary "ideological state apparatus" (an institution whose role is not political or administrative, but that still manages to influence us). It makes people see the world a certain way, and to accept certain identities. In this case, although it has less to do with technology, the mother and child are put into their respective positions due to the covert influence of the education system. The idea of power relations can be discussed here too, because what's interesting about this dynamic is that although the mother is placed into this position, it is not an unenjoyable one. She takes pleasure from preparing these lunchboxes for the child, as they are the way for the Japanese mother to express her identity and commitment through her food. So, a person's autonomy is not completely lost through this wielding of power, although they are ultimately still restricted by these rules.

The other reading we focused on this week was Sloterdijk's chapters from "Critique of Cynical Reason". What I found interesting was a reference that he makes in the chapter on artificial limbs. He mentions that in some textbooks, "a highly apposite image of the human being emerges: Homo prostheticus". Is this idea of a new species of human being a relative of the cyborg? Perhaps, since he is part machine and part organism. I actually plan to talk about transhumanism in my research paper, and this passage sort of touches on this matter. The fact that some textbooks and writings give humans with prosthetic limbs a whole new name implies that they are post-human beings.

On the topic of biopower & biopolitics, it might be interesting to bring up the issue of cancer drugs not being available to everyone in Canada. "Government red tape" apparently has strict rules about who gets the drugs and who doesn't, which is incredibly unfair in a situation that may be a matter of life and death for the cancer patient. An article about this issue can be read here. Another example of power over drugs is the Ontario Drug Benefit Formulary, which can be read about here.

Friday, November 17, 2006

How coincidental is this? The week that we talk about stem cells and biomedicine in class, is the week that I come across articles on these topics. Or, maybe it's just that these topics are so prevalent in current events that they're practically unavoidable.

Mahowald's article talks about different uses of cloning, and the third of these is "therapeutic cloning, where the therapy is not intended to produce children". I guess this method can be applied to this article I found in Thursday's Toronto Star (A14) titled "Stem cells ease muscle disease in dogs". The author says that "stem cell injections worked remarkably well at easing muscular dystrophy in a group of golden retrievers". The difference between this article and Mahowald's article is that the Toronto Star article indicates that they used "stem cells taken from the affected dogs or other dogs, rather than from embryos". This article is an ideal example of stem cell research that does not raise the ethical issue of killing embryos. Stem cells retrieved from already living organisms are still effective in alleviating symptoms of the disease.

Right underneath this article was another article titled "Heart valves grown in lab experiment". Here, it's said that "scientists for the first time have grown human heart valves using stem cells from the fluid that cushions babies in the womb". Apparently, they're to be implanted into babies with heart defects after it is born. Again, this article is an example of NOT using embryonic stem cells to aid medical problems. When Mahowald says that "embryonic stem cells ... may provide the only effective therapy for some diseases", she seems to be overlooking medical conditions that could benefit from non-embryonic stem cells.

We also looked at Wolpe's article on genes and Jewish beliefs. On the opposite side of the newspaper where the previous 2 articles came from, is an article about DNA; "Scientists crack Neanderthal DNA". From their research, the scientists say that the Neanderthal species separated from humans 370,000 years ago. This is interesting and these findings seem to evoke as much excitement in researchers as much as finding out what particular DNA account for certain traits in people.

In Wolpe's article, there is a quote that "genes are our our hope for the future; the search for DNA has become not a scientific endeavor but a holy mission, a Quest". Sure, the quest for DNA is rooted in our hopes for the future, but as this Toronto Star article shows, it is also associated with learning more about our past. Its research in the archeological field might not be as practical as its research in biomedicine, but it can still be pretty darn interesting.

Mahowald's article talks about different uses of cloning, and the third of these is "therapeutic cloning, where the therapy is not intended to produce children". I guess this method can be applied to this article I found in Thursday's Toronto Star (A14) titled "Stem cells ease muscle disease in dogs". The author says that "stem cell injections worked remarkably well at easing muscular dystrophy in a group of golden retrievers". The difference between this article and Mahowald's article is that the Toronto Star article indicates that they used "stem cells taken from the affected dogs or other dogs, rather than from embryos". This article is an ideal example of stem cell research that does not raise the ethical issue of killing embryos. Stem cells retrieved from already living organisms are still effective in alleviating symptoms of the disease.

Right underneath this article was another article titled "Heart valves grown in lab experiment". Here, it's said that "scientists for the first time have grown human heart valves using stem cells from the fluid that cushions babies in the womb". Apparently, they're to be implanted into babies with heart defects after it is born. Again, this article is an example of NOT using embryonic stem cells to aid medical problems. When Mahowald says that "embryonic stem cells ... may provide the only effective therapy for some diseases", she seems to be overlooking medical conditions that could benefit from non-embryonic stem cells.

We also looked at Wolpe's article on genes and Jewish beliefs. On the opposite side of the newspaper where the previous 2 articles came from, is an article about DNA; "Scientists crack Neanderthal DNA". From their research, the scientists say that the Neanderthal species separated from humans 370,000 years ago. This is interesting and these findings seem to evoke as much excitement in researchers as much as finding out what particular DNA account for certain traits in people.

In Wolpe's article, there is a quote that "genes are our our hope for the future; the search for DNA has become not a scientific endeavor but a holy mission, a Quest". Sure, the quest for DNA is rooted in our hopes for the future, but as this Toronto Star article shows, it is also associated with learning more about our past. Its research in the archeological field might not be as practical as its research in biomedicine, but it can still be pretty darn interesting.

Sunday, November 12, 2006

So, last class we discussed Campbell's article. There is a section in this article that I must comment on: "Children: Choice or gift?" ... in one particular passage, the author notes that:

So, last class we discussed Campbell's article. There is a section in this article that I must comment on: "Children: Choice or gift?" ... in one particular passage, the author notes that:"Children are never completely products of deliberate and designed autonomous decisions. The child may instead be a surprise, whose conception, gestational development, and birth evoke in parents basic sentiments of awe and wonder".

This is an overly idealistic way of perceiving the gift of life. Of course, this described situation can apply to many families, but what of women who are raped? High school girls whose partners' condoms broke? Women who live in such abysmal conditions and must have unprotected sex with their "lover" to keep having a roof over their heads? Rapists during war who rape women to infiltrate the "racial purity" of a nation? Children who are put up for adoption? ... No, children are not always "autonomous" decisions, but they also do not always evoke "awe and wonder" in the parents due to the differing conditions that children are conceived in.

We also discussed McKenny's article -- indeed, "when the statement turns to plants, the nature of moral concern shifts in a way that makes it clear that moral standing is ascribed not to nature as a whole but only to part of it". Sure, religion tends to oppose cloning humans and animals, but it's fine to "play God" with plants? I guess we can look to Gregor Mendel as an example of this exception. He was the monk who crossbred peas to investigate inheritance traits, and from this experiment, was interested in discovering more about DNA & the Double Helix. No wait... DNA/Double Helix is Watson and Crick. Anyway, Mendel is an example that science and religion can cross boundaries because of life experience (he "worked as a gardener in his childhood"). Sometimes you can't avoid it. Heck, my friend's parents are devout Catholics who work at an immunology & vaccination research company.

I recall we also had a discussion about taking religion out of the politican spectrum. Perhaps this is a bit more plausible in the Canadian government, but looking at American politics, this idea is almost laughable. Has anyone ever heard of the TV show "30 Days"? I didn't mention this in class... from the creator of "Supersize Me", it's a show where people live 30 days in a lifestyle that is completely different from their own, to gain insight, perspective, or simply just learn from it.

I recently saw an episode about an atheist living with a Christian family. They talked about American money in one part of the episode, and the Christian's remarks really remind me of what we talked about regarding (some) Christians and their "don't like it, get out" comments. I have the episode on my computer so here is the entire conversation. Typing this out will be fun:

Atheist: How about the fact that Brenda and the rest of us spend money that has God stamped on it? Does the government have a legitimate right to make a theological statement for everybody?

Christian: Well we don't really care -

Atheist: What if it said on your dollar bills and your coins, "There is no God"?

Christian: Ours says "In God We Trust" and we actually like that.

Atheist: What would you say if it said "There is no God"?

Christian: *shakes head* It says "In God We Trust".

Atheist: What would you say if it said "There is no God"?

Christian: It says "In God We Trust".

Atheist: I'm asking you, what if it said "There is no God"? I'm asking you a hypothetical, what do you think of that?

Christian: I live here, in the US, and it says "In God We Trust".

Atheist: For the record, I would oppose "There is no God" on our money, because I respect the right of Christians and other believers to have their beliefs, without having to carry around money that has something on it which is a slogan that they really deeply disgree with? I'm willing to let you guys have your religious liberty, but you're not willing to let me have mine.

Christian: I guess it doesn't bother me that it's on the money. If it bothers you, move. I mean...

Atheist: You see? This is a typical Christian -- this is a Christian country, if you don't like it then get out. That's terrible.

Christian: If it bothers you that much then I don't know what to tell you to do.

It's an interesting episode indeed.

Thursday, November 02, 2006

Athena, Athena, Athena. If it were not for yesterday's seminar I would have drowned in her essay of incoherence. Thanks guys, for clearing some of it up. Seems like she pressed Shift-F7 one too many times while writing this essay... kidding.

"For the more technology seeks to put things in their proper place, the less proper those places turn out to be, the more displaceable everything becomes and the more frenetic becomes the effort to reassert the propriety of the place as such" (p. 135).

This notion I guess, is applicable to many technologies. The purpose of many technological advances (genetic engineering, robotics, internet, GPS, etc.) is to enhance the quality or efficiency of life. But if overdone, these technologies become displaced and the intention for their original use vanishes. Genetic engineering wants to help cure disease, but it assists parents in choosing the sex of their baby. Robots are supposed to create efficiency so humans are relieved of responsibility, but what about the loss of employment for those whose living depends on such seemingly mundane work? I'm not sure if I am going in the right direction, but this is the impression that I get.

"The challenge ... is to rethink 'technology' ... as a plural, dispersed, and discontinuous engagement as it is enacted in the following registers: biopolitical technologies ... technologies of the body ... and technologies of the self." (144-145).

So, we should consider technology in the context of this jumbled interaction. Again, this reminds me of the idea of "brain death" and whether to end someone's life just because their "higher consciousness" is dead, yet their body is still alive. Who is the gatekeeper that decides what to do with the body? Another example is whether it is ethical to utilize a human cadaver for profane yet enlightening research purposes such as "Body Worlds 2" (at the Science Centre), although that individual when alive, only consented to research in the private sphere. What would they say if their cadaver was subjected to such scrutiny and amusement by children, and perhaps the disgust of parents? Would their dead self consent to this if they perceived it as a learning experience for society?

By the way, here is a link to the Japanese android article from CityNews.ca:

http://www.citynews.ca/news/news_4911.aspx

"The Japanese government believes the market for service robots will reach an astounding $10 billion within the next decade."

To incorporate this subject into Athena's article, yes this technology will bring efficiency to Japan, but its implications on the rest of society must be looked at as well.

We also discussed 'open forums' and 'open sources' in class -- an article in the Toronto Star today talked about York University's implementation of "open source" Wiki-style systems with which students can edit each other's work:

"They are tuned into this open-source movement ... Now students in selected classes are submitting written content, including assignments, to the mini-Wikis, subject to input from classmates ... 'For some they might not be comfortable with the idea that they are not handing their work to me but they are handing their work to the entire class. it shifts how they think of themselves and their work in class. They come to think about knowledge production as a collaborative and public process."

Perhaps we can view the blogging component of this course as an open source forum as well. Although not nearly as interactive in that we edit each other's posts, the idea that we are putting our thoughts out there for others' scrutiny and commentary is somewhat similar to the Wiki concept.

Link to Wiki article is here.

"For the more technology seeks to put things in their proper place, the less proper those places turn out to be, the more displaceable everything becomes and the more frenetic becomes the effort to reassert the propriety of the place as such" (p. 135).

This notion I guess, is applicable to many technologies. The purpose of many technological advances (genetic engineering, robotics, internet, GPS, etc.) is to enhance the quality or efficiency of life. But if overdone, these technologies become displaced and the intention for their original use vanishes. Genetic engineering wants to help cure disease, but it assists parents in choosing the sex of their baby. Robots are supposed to create efficiency so humans are relieved of responsibility, but what about the loss of employment for those whose living depends on such seemingly mundane work? I'm not sure if I am going in the right direction, but this is the impression that I get.

"The challenge ... is to rethink 'technology' ... as a plural, dispersed, and discontinuous engagement as it is enacted in the following registers: biopolitical technologies ... technologies of the body ... and technologies of the self." (144-145).

So, we should consider technology in the context of this jumbled interaction. Again, this reminds me of the idea of "brain death" and whether to end someone's life just because their "higher consciousness" is dead, yet their body is still alive. Who is the gatekeeper that decides what to do with the body? Another example is whether it is ethical to utilize a human cadaver for profane yet enlightening research purposes such as "Body Worlds 2" (at the Science Centre), although that individual when alive, only consented to research in the private sphere. What would they say if their cadaver was subjected to such scrutiny and amusement by children, and perhaps the disgust of parents? Would their dead self consent to this if they perceived it as a learning experience for society?

By the way, here is a link to the Japanese android article from CityNews.ca:

http://www.citynews.ca/news/news_4911.aspx

"The Japanese government believes the market for service robots will reach an astounding $10 billion within the next decade."

To incorporate this subject into Athena's article, yes this technology will bring efficiency to Japan, but its implications on the rest of society must be looked at as well.

We also discussed 'open forums' and 'open sources' in class -- an article in the Toronto Star today talked about York University's implementation of "open source" Wiki-style systems with which students can edit each other's work:

"They are tuned into this open-source movement ... Now students in selected classes are submitting written content, including assignments, to the mini-Wikis, subject to input from classmates ... 'For some they might not be comfortable with the idea that they are not handing their work to me but they are handing their work to the entire class. it shifts how they think of themselves and their work in class. They come to think about knowledge production as a collaborative and public process."

Perhaps we can view the blogging component of this course as an open source forum as well. Although not nearly as interactive in that we edit each other's posts, the idea that we are putting our thoughts out there for others' scrutiny and commentary is somewhat similar to the Wiki concept.

Link to Wiki article is here.